As the Manitoba Government contemplates the shape and form of its carbon pricing and green plan, heeding the words of perhaps our greatest public intellectual might be prudent.

“We shape the tools then the tools shape us,” said Marshal McLuhan, the Kelvin High School and University of Manitoba alumnus and eminent cultural theorist. He meant that the tools we create can be very useful, but still carry unintended negative consequences, so the tool-maker’s foresight and breadth of vision matter mightily.

McLuhan’s reign—when he held court at his Centre for Culture and Technology at the University of Toronto from the early 1950s until 1979—coincided with mass consumption of automobiles and television. His observations on how these technologies were re-shaping society, the environment, and especially our psychology were profound. In Manitoba, it’s been arguably the surveyor’s rod and the drainage dredge that have proved to be the most impactful technologies.

The Dominion Land Survey (DLS), the largest integrated survey system in the world, began in 1871 to promote settlement via a quarter-section homesteading model. University of Alberta environmental historian (and former Winnipegger) Shannon Stunden Bower has documented the broader cultural and environmental implications of DLS—a settler culture devoted to an ethos of land improvement by clearing forest and bush and draining marsh and wetlands by constructing / developing / implementing / building an ever-more comprehensive drainage network. Of course, the benefits of DLS must be acknowledged. Agriculture has flourished in Manitoba for almost 150 years and remains a fundamental pillar of Manitoba’s economy. However, the unintended consequences and vulnerabilities of the infrastructure networks that have grown up alongside the DLS are also occasionally exposed.

In the aftermath of the 1930s dust bowl, the Prairie Farm Rehabilitation Administration was established by the federal government to repair much of the damage wrought, notably by planting trees and by building small-scale water retention projects peppered across all three Prairie provinces. More recently, the 2011 Assiniboine River flood revealed other vulnerabilities—over $1 billion dollars of damage to rural infrastructure. Section roads, highways, culverts, and bridges were blown apart from a climate shock on a heavily DLS modified landscape that was not designed to store water. And then, within a few months, much of southern Manitoba experienced an agricultural drought. Some sections of land were under both flood and drought insurance claims that year, and we are still dealing with the catastrophic economic impacts of 2011.

Financing resilience

Though 2011 was declared a one-in-300-year event at the time, that’s very unlikely to be the case. The best available climate science for the region, assembled by the Prairie Climate Atlas, projects a much higher frequency oscillation between flood and drought conditions. Deeper ditches and more tile drainage do not take these risks off the table; they merely transmit flood risk downstream and largely exacerbate drought risk.

The provincial sales tax increase was justified as necessary to construct the infrastructure needed to de-risk us from more 2011-type events. Of the major infrastructure projects in the queue for federal and provincial co-funding, none take a nickel of 2011-type climate risk off the table, nor do they address the converse risk—drought. The climate and infrastructure policy narratives in Manitoba should be better connected. The logic for pricing carbon is that every jurisdiction must share the burden of reducing global climate risk. How carbon revenues should be optimally re-invested is an open question in environmental economics and the subject of recent public consultations. The logic for re-investing at least part of our carbon revenues in our own risk reduction should be pretty obvious, particularly when it can leverage infrastructure investment with high economic multipliers that broaden the tax base.

What solutions look like

International capital markets that have identified the problem are looking for solutions, and Manitoba needs to be at the table. In April, Globe Capital hosted a conference in Toronto attended by four federal cabinet ministers. The conference addressed how to unlock an estimated $90 trillion dollars in global investment to fund infrastructure that de-carbonizes and climate-proof our economies. In Manitoba, we’re increasingly confident that we know what the solutions look like—they’re decentralized and truly green infrastructure.

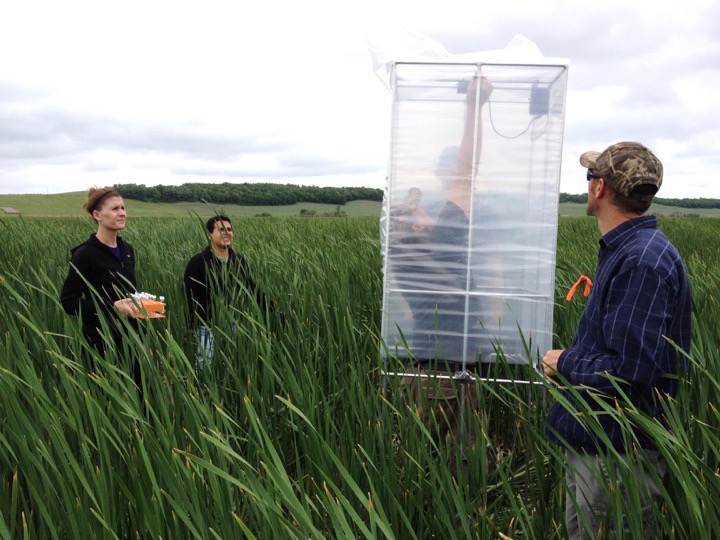

Since 2012, the International Institute for Sustainable Development has collaborated with the LaSalle-Redboine Conservation District to manage a multi-functional water retention project known as Pelly’s Lake near Holland, Man. Originally conceived to mitigate flood and drought risk, it’s now used to harvest high-value biomaterial and bioenergy and to intercept and recycle phosphorus that would otherwise foul Lake Winnipeg. We’ve also confirmed that harvesting from the site enhances its ability to absorb greenhouse gases, while improving habitat conditions.

Pelly’s Lake creates a stack of risk reduction, economic, and environmental benefits that make it a compelling investment. Moreover, it achieves all the environmental objectives the Manitoba Government has prioritized through the proposed Alternative Land Use Services (ALUS) program. The only issue is that hundreds of Pelly’s Lakes will be needed across the province. But they’re out there and will only occupy a small fraction of the agricultural landscape, turning some of our least productive land into super-productive risk management nodes. There are no more Winnipeg floodways to build, and even if there were, such conventional infrastructure spends wouldn’t provide the co-benefits that make the green infrastructure and cleantech investment option the best one for long-term economic development.

Fundamentally, climate policy and infrastructure policy should be linked, and the jurisdictions that do so with foresight, sophistication, and resilience in mind will (sustainably) rocket to the top of the investment queue. Let’s shape these tools wisely, for they will shape us for the century to come.

Henry “Hank” Venema is the director of planning with the Prairie Climate Centre and the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD). Venema is the chair of the 2017 Canadian Water Summit, produced annually by ReNew Canada’s sister publication Water Canada.