The clock is ticking down until next year’s Pan American and Parapan American games in Toronto—and everything is on track for what will be the largest multi-sport event ever to be held in Canada.

The Toronto 2015 Pan Am Games will be held July 10 to 26, 2015, with the Parapan Am Games from August 7 to 15, 2015. Athletes from 41 countries will compete in 51 sporting events, at least 16 of which are qualifiers for the Olympics. Athletes, coaches, support staff, and officials will number more than 10,000, with thousands of spectators also expected to attend. The event involves more than 30 venues, 16 municipalities, five partners, and 20,000 volunteers. Coinciding with the Games will be a unique 35-day celebratory festival that will feature more than 1,000 performers, with downtown Toronto’s Nathan Phillips Square serving as “celebration central.”

The Games will unarguably be a gigantic affair, but how does an event of this size come together? By using teams—and the guiding hand of experts. There are 10 divisions, with 48 departments among them, tracking more than 100 projects with more than 1,600 milestones and deliverables in the master plan. Risk management aspects that must be managed range from health, safety, and the environment, to security, incident response, and Games readiness, involving involve everything from vendor contract reviews, internal audits, insurance claims administration, and post-event analysis.

Managing the risk management behind the endeavour is Joanna Makomaski, Toronto 2015 VP of enterprise risk management (ERM) and an international presenter on best risk management practices. Risk management can be boiled down to having proactive systems in place so “you’re ready to respond to [issues] before, during, and after an event,” she says. The same systems and principles can be applied to any event or organization. In the case of the Games, it’s what Makomaski calls a start-up organization. “With this start-up, the organization grows quickly, operates for a short period of time, then dissolves quickly afterward,” she explains. “The frameworks are implemented differently than you would implement them in, for example, a 150-year-old organization that wants to expand operations or go in a new direction.”

The first step in risk management involves risk identification. “To do this, we leverage the functional area experts around us, asking what could derail them from providing their services,” Makomaski explains. Described risk events are then evaluated for their severity and likelihood before being prioritized. She makes sure everyone involved has practical and accessible tools to do this, like spreadsheets, guidelines, templates, and checklists. This makes it easy for everyone to understand and consistently quantify the likelihood and severity of various outcomes, and for her to gather up this information, “from a spectator injury to preparing for events like heavy winds or flooding,” she says.

The next step is to put plans in place to handle risks, a big step toward achieving “risk readiness.” For example, a power outage is a scenario that could occur, and contingency plans are being created involving back-up generation and lines of communication with utilities. “Another possible situation that we will watch closely is extreme summer heat, so in that case, we look at things like water availability, shade, air conditioning, medical crew availability, and so on,” Makomaski says. “It’s all about being well prepared.”

Part of validating the risk analyses involves comparing this Games event to other Pan Am games, summer Olympics, and other events that have been held in the Greater Toronto Area. Makomaski says she has met with people that have run other summer games to gain insight into some of their experiences, but explains that each situation is different, and some risk-management practices used in one place are not always applicable in another or need to be applied much differently.

For example, the last Pan Am Games were held in October 2011 in Guadalajara, Mexico. The ongoing drug war in that region meant ongoing violence was a significant risk at the Games, and after some countries including Canada expressed concerns about safety and security, the organizers and government made sure police and members of the armed forces were on hand throughout the event. In Toronto, or anywhere else for that matter, the cultural, locational, and jurisdictional differences are different.

At this point in time, risk identification and analysis are complete, including insurance procurement, and policy and procedures for contingencies are now being worked on. By this fall, the organization will be moving into Games-readiness mode, involving rehearsals—a loose term to describe readiness table top exercises, technical rehearsals, and even test events.

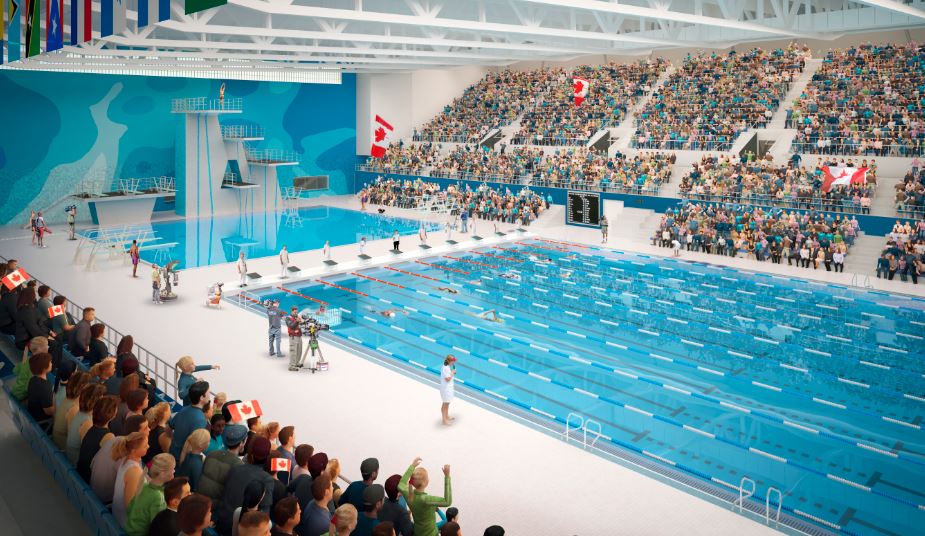

Facilities for the Games

One of the 10 divisions preparing and executing the 2015 Pan Am/Parapan Am Games is focused entirely on facilities—which ones in the region will be used, how they will be modified, and how they will transition back to regular use after the Games are done.

A section of the West Don Lands community will be used as the Toronto 2015 Pan/Parapan American Games Athletes’ Village. Unlike many athletes’ village projects which are built to house competitors during major athletic events and then converted to other uses following the games, Toronto’s Athletes’ Village project is accelerating the building of a community that was already planned and under development. It’s an alternative finance project being built by Dundee Kilmer Developments Ltd., a consortium whose team includes Dundee Realty Corp., Kilmer Van Nostrand Co. Ltd., EllisDon Corp., Ledcor Design Build (Ontario) Inc., Brookfield Financial Corp., and architects Kuwabara Payne McKenna Blumberg, Daoust LeStage Inc., and TEN Arquitectos. “We have brought together an outstanding team to design, build, and finance the award-winning Canary District,” Dundee Kilmer Developments’ Ken Tanenbaum said in a press announcement. “A brilliantly planned urban community in the heart of Toronto’s downtown east, Canary District will be a lasting legacy.”

Development of the West Don Lands, including the section that will house athletes and officials during the Games, is being guided by Waterfront Toronto’s West Don Lands Precinct Plan. Last year, at the Athletes’ Village’s 50-per-cent completion milestone, Waterfront Toronto president John Campbell said, “Locating the Athletes’ Village in the West Don Lands has significantly accelerated Waterfront Toronto’s revitalization of the area and is a very positive legacy of hosting the Games. Following the Games, the West Don Lands will be a beautifully designed mixed-use community adding vibrancy to this long-neglected area of the city.” Units will be retrofitted—for example, existing kitchen counter tops will be removed and granite installed—and sold as residential units.

Most of the sporting facilities to be used already exist, but a few like the Centennial Park Pan Am BMX Centre in Etobicoke are being constructed. This contrasts with Pan Am Mexico 2011, for example, where of the roughly 35 venues used, most were newly built for the Games. Most facilities to be used during Toronto 2015 are owned by municipalities while others belong to entities like universities (such as the University of Toronto’s field hockey field).

“The changes that will be required at each venue range from minor to significant,” Toronto 2015 VP of venue management and events services Jan Damnavits says. The Toronto team will begin adding temporary infrastructure to each facility in May 2015, swinging into high action and modifying all venues simultaneously. He says planning is going well. “As soon as the competition at a facility ends, decommissioning begins immediately—that evening or next day,” Damnavits notes. “That way, normal use can begin as soon as possible.”

The banners will be taken down, the facilities will go back to normal, and it will be like the Games never happened. Except that they will have happened—the biggest Pan Am/Parapan Am Games ever, in Canada’s biggest city.

Treena Hein is a freelance writer based in Pembroke, Ontario.